![]() The Battle of Marston Moor was the pivotal event that convinced James Graham, Earl of Montrose, to defect from the side of the Scottish Covenanters and raise an army in support of King Charles. During the summer of 1644, Montrose traveled through the Highlands calling on the Highland clansmen to form an army. His army eventually came to include many Highlanders, some Scottish expatriates from Ireland, a group of mercenaries and a few Royalist lairds from the Lowlands.

The Battle of Marston Moor was the pivotal event that convinced James Graham, Earl of Montrose, to defect from the side of the Scottish Covenanters and raise an army in support of King Charles. During the summer of 1644, Montrose traveled through the Highlands calling on the Highland clansmen to form an army. His army eventually came to include many Highlanders, some Scottish expatriates from Ireland, a group of mercenaries and a few Royalist lairds from the Lowlands.

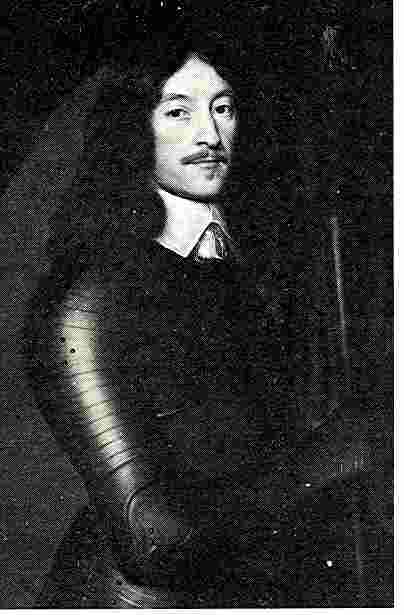

James Graham, Marquis of Montrose

~ Source unknown.

![]() With his army of less than two thousand men, Montrose captured the city of Dumfries. But that was the only notable event for the new Royalist army until it was joined by a group of Irish soldiers.

With his army of less than two thousand men, Montrose captured the city of Dumfries. But that was the only notable event for the new Royalist army until it was joined by a group of Irish soldiers.

![]() The Irish soldiers who would come to join with Montrose’s army were Irish Catholics led by Alasdair MacColla MacDonald, of Clan Donald. Alasdair was the son of MacDonald of Colonsay, a kinsman of the Earl of Antrim. The two thousand troops he brought with him from Ireland were battle-hardened and well armed. They landed at Ardnamurchan in June and were soon joined by nearly a thousand Hughlanders. Bearing age-old grudges against the Clan Campbell, Alasdair lost no time in thundering through the Campbell lands of Argyll, looting and destroying as they went. At Blair Atholl, in August, Alasdair and Montrose crossed paths and the two hit it off immediately, joining forces as a formidable Royalist army.

The Irish soldiers who would come to join with Montrose’s army were Irish Catholics led by Alasdair MacColla MacDonald, of Clan Donald. Alasdair was the son of MacDonald of Colonsay, a kinsman of the Earl of Antrim. The two thousand troops he brought with him from Ireland were battle-hardened and well armed. They landed at Ardnamurchan in June and were soon joined by nearly a thousand Hughlanders. Bearing age-old grudges against the Clan Campbell, Alasdair lost no time in thundering through the Campbell lands of Argyll, looting and destroying as they went. At Blair Atholl, in August, Alasdair and Montrose crossed paths and the two hit it off immediately, joining forces as a formidable Royalist army.

![]() On 1 September, Montrose attacked an army of Covenanters under the command of David Wemyss, Lord Elcho near the town of Tippermuir, west of Perth. Although the Covenanter army of Lord Elcho outnumbered the Royalists, Alasdair had trained his Irishmen and their new Highland compatriots the battle tactic of the ‘Highland Charge.’ In the Highland Charge, the infantry, armed with muskets, would advance to within a hundred yards of the enemy. They would fire a single volley, and then drop the weapons to the ground and charge forward with their broadswords drawn.

On 1 September, Montrose attacked an army of Covenanters under the command of David Wemyss, Lord Elcho near the town of Tippermuir, west of Perth. Although the Covenanter army of Lord Elcho outnumbered the Royalists, Alasdair had trained his Irishmen and their new Highland compatriots the battle tactic of the ‘Highland Charge.’ In the Highland Charge, the infantry, armed with muskets, would advance to within a hundred yards of the enemy. They would fire a single volley, and then drop the weapons to the ground and charge forward with their broadswords drawn.

![]() The Covenanters were defeated at Tippermuir, and Montrose continued on to Aberdeen, which his army sacked. The Irishmen and Highlanders killed, raped and looted the townsfolks in and orgy that lasted three days.

The Covenanters were defeated at Tippermuir, and Montrose continued on to Aberdeen, which his army sacked. The Irishmen and Highlanders killed, raped and looted the townsfolks in and orgy that lasted three days.

![]() Montrose then turned westward and marched through the lands traditionally held by the Campbells, and home of Archibald Campbell, Earl of Argyll. The army was augmented by clansmen from the Macleans and the Macdonalds, who were probably more interested in settling old scores with the Campbells than in assisting the Royalist Cause. Montrose arrived on Argyll’s castle at Inveraray with such speed and surprise that the Earl was startled at his dinner table, and only barely escaped by boat across Loch Fyne. In February, 1645, after an arduous march through heavy snows, Montrose and his army arrived at Inverlochy, where he again routed the Campbells and the Earl of Argyll along with his Covenanter supporters. Montrose chased Argyll through Lorn, Glencow and Lochaber and on to the shores of Loch Ness. In March, he attacked the city of Dundee, succeeding in breaching the stone walls of that town. In May, Montrose scored another victory over the Covenanters near the Moray Firth at Auldearn, and then in July, he again routed them at Alford, near Aberdeen. By August, 1645 the independent Royalist army under Montrose had defeated a Covenanter army at Kilsyth and had occupied the city of Glasgow. Montrose had believed that he would be able to gain supporters in the Lowlands, but things were not destined to work out that way. And then, in September, Montrose’s winning streak came to an end.

Montrose then turned westward and marched through the lands traditionally held by the Campbells, and home of Archibald Campbell, Earl of Argyll. The army was augmented by clansmen from the Macleans and the Macdonalds, who were probably more interested in settling old scores with the Campbells than in assisting the Royalist Cause. Montrose arrived on Argyll’s castle at Inveraray with such speed and surprise that the Earl was startled at his dinner table, and only barely escaped by boat across Loch Fyne. In February, 1645, after an arduous march through heavy snows, Montrose and his army arrived at Inverlochy, where he again routed the Campbells and the Earl of Argyll along with his Covenanter supporters. Montrose chased Argyll through Lorn, Glencow and Lochaber and on to the shores of Loch Ness. In March, he attacked the city of Dundee, succeeding in breaching the stone walls of that town. In May, Montrose scored another victory over the Covenanters near the Moray Firth at Auldearn, and then in July, he again routed them at Alford, near Aberdeen. By August, 1645 the independent Royalist army under Montrose had defeated a Covenanter army at Kilsyth and had occupied the city of Glasgow. Montrose had believed that he would be able to gain supporters in the Lowlands, but things were not destined to work out that way. And then, in September, Montrose’s winning streak came to an end.

![]() Following the Battle of Naseby in which the New Model Army scored a major victory over the Royalist army, David Leslie returned northward with his army of four thousand Covenanters. At Philiphaugh, in the Borders, Leslie surprised Montrose and inflicted a heavy defeat on his independent Royalist army.

Following the Battle of Naseby in which the New Model Army scored a major victory over the Royalist army, David Leslie returned northward with his army of four thousand Covenanters. At Philiphaugh, in the Borders, Leslie surprised Montrose and inflicted a heavy defeat on his independent Royalist army.