![]() The Liberty Pole, an object of no small significance was embraced by the American rebels throughout the English Colonies during the Revolutionary War period. It was an object that originated in the ancient Greek and Roman Empires, and which would be utilized to announce and proclaim Liberty even after the American Revolutionary War had ended. The French, when they overthrew their sovereign, embraced the Liberty Pole with as much fervor as their American cousins.

The Liberty Pole, an object of no small significance was embraced by the American rebels throughout the English Colonies during the Revolutionary War period. It was an object that originated in the ancient Greek and Roman Empires, and which would be utilized to announce and proclaim Liberty even after the American Revolutionary War had ended. The French, when they overthrew their sovereign, embraced the Liberty Pole with as much fervor as their American cousins.

![]() So what exactly was a Liberty Pole? The Liberty Pole, while being a very simple object, was one which aroused passions and rallied Patriots to espouse and embrace liberty.

So what exactly was a Liberty Pole? The Liberty Pole, while being a very simple object, was one which aroused passions and rallied Patriots to espouse and embrace liberty.

![]() The word ‘rally’ perfectly describes the function of the Liberty Pole because the raising of one was intended to induce townsfolk to rally around it. Once the crowd began to swell in numbers, a spokesman for the local contingent of the Sons of Liberty, Committee of Safety or other Patriot group would speak to the crowd, exhorting them to join the Patriot Cause or to take some other sort of action. The raising of the Liberty Pole was, at once, a beacon to call forth those who hungered for liberty and a symbol of defiance to the established government. In most cases that have been recorded, the local authorities would have a Liberty Pole destroyed within a few days of it being erected.

The word ‘rally’ perfectly describes the function of the Liberty Pole because the raising of one was intended to induce townsfolk to rally around it. Once the crowd began to swell in numbers, a spokesman for the local contingent of the Sons of Liberty, Committee of Safety or other Patriot group would speak to the crowd, exhorting them to join the Patriot Cause or to take some other sort of action. The raising of the Liberty Pole was, at once, a beacon to call forth those who hungered for liberty and a symbol of defiance to the established government. In most cases that have been recorded, the local authorities would have a Liberty Pole destroyed within a few days of it being erected.

![]() The image above shows America on the right side, holding a flag staff which doubles as a Liberty Pole. Anyone viewing this cartoon knew exactly what was being implied by the cap on the pole which was being held by the ‘native’ figure of America.

The image above shows America on the right side, holding a flag staff which doubles as a Liberty Pole. Anyone viewing this cartoon knew exactly what was being implied by the cap on the pole which was being held by the ‘native’ figure of America.

![]() There were only two elements of the Liberty Pole: 1.) a non-descript wooden pole, and 2.) a Phrygian Cap. At times a flag, or standard, might be attached to the pole, but that was not the common practice.

There were only two elements of the Liberty Pole: 1.) a non-descript wooden pole, and 2.) a Phrygian Cap. At times a flag, or standard, might be attached to the pole, but that was not the common practice.

![]() The pole was most often wooden, and although sometimes available already cut, it was more than likely hewn for the purpose from a long, straight tree with a base diameter of a foot or so. The longer the pole, the better ~ twelve to sixteen feet was desireable. A tall pole might be seen by more people across fields, and therefore attract more. It would be set into a hole dug about three or four feet deep so that it would be sturdy and stand for some period of time ~ if allowed.

The pole was most often wooden, and although sometimes available already cut, it was more than likely hewn for the purpose from a long, straight tree with a base diameter of a foot or so. The longer the pole, the better ~ twelve to sixteen feet was desireable. A tall pole might be seen by more people across fields, and therefore attract more. It would be set into a hole dug about three or four feet deep so that it would be sturdy and stand for some period of time ~ if allowed.

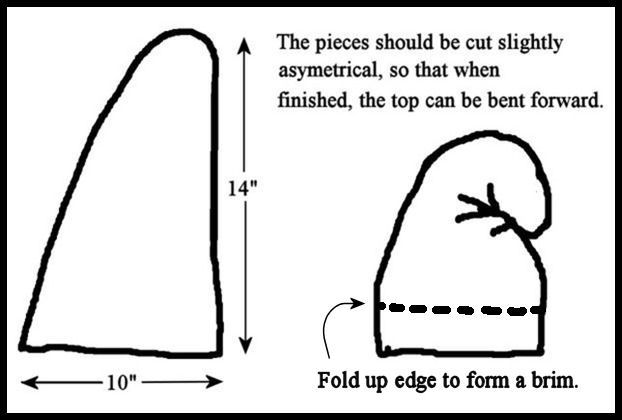

![]() The cap that was placed over the top of pole was called a ‘Phrygian Cap.’ The placement of the cap on the top of the pole is the element that changed the piece of wood from a simple ‘pole’ to a ‘Liberty’ pole. The Phrygian cap comes down through history from the days of the ancient Greek Empire. The kingdom of Phrygia was located in the west-central part of Anatolia, which is present-day Turkey. The Phrygian weavers made a distinctive woven cap, usually of red wool or felt. It was conical in shape, but the two sides of the cone were not of equal length. In fact the one side was basically perpendicular to the base line, while the other side was longer, stretching from the base line to merge with the opposite end of the shorter side. The cap usually had a turned up brim. The shorter side of the conical shape was worn toward the front of the head. The result, when worn, was that the tip of the cone would fall over, forward. The modern-day comic characters called ‘smurfs’ wear this distinctive, forward-bent cone-shaped cap. [Although similar to the red and white ‘elf cap’ with the long pointy tip (ending in a puffy ball) that hangs down to the back, or to the side, which were worn by ‘Santa’s Elves’ at their workshop at the North Pole, the Phrygian cap was not worn with the hang-over in the backward direction, nor was it ever multi-color.]

The cap that was placed over the top of pole was called a ‘Phrygian Cap.’ The placement of the cap on the top of the pole is the element that changed the piece of wood from a simple ‘pole’ to a ‘Liberty’ pole. The Phrygian cap comes down through history from the days of the ancient Greek Empire. The kingdom of Phrygia was located in the west-central part of Anatolia, which is present-day Turkey. The Phrygian weavers made a distinctive woven cap, usually of red wool or felt. It was conical in shape, but the two sides of the cone were not of equal length. In fact the one side was basically perpendicular to the base line, while the other side was longer, stretching from the base line to merge with the opposite end of the shorter side. The cap usually had a turned up brim. The shorter side of the conical shape was worn toward the front of the head. The result, when worn, was that the tip of the cone would fall over, forward. The modern-day comic characters called ‘smurfs’ wear this distinctive, forward-bent cone-shaped cap. [Although similar to the red and white ‘elf cap’ with the long pointy tip (ending in a puffy ball) that hangs down to the back, or to the side, which were worn by ‘Santa’s Elves’ at their workshop at the North Pole, the Phrygian cap was not worn with the hang-over in the backward direction, nor was it ever multi-color.]

![]() During the time of the ancient Greek Empire, when a slave gained his freedom, he would wear a conical shaped cap as a sign that he had gained his freedom through legal means. The original cap used for this purpose was called a Pileus cap. It was a simple cone shaped, brimless felt cap. The slave being freed would undergo a ceremony in which he would have his head shaved and the pileus placed on his bald head. The slave would be touched on the shoulder with a rod called a vindicta, and he would henceforth be a free man. Afterward, if the freed slave did not wear the pileus cap, he ran the risk of being taken into custody and forced into slavery again. The custom became a hallmark of the ancient Roman Empire as the Roman Empire overran and assimilated the culture of the ancient Greeks. As time went on, the Phrygian cap, worn in Anatolia by the common man, became confused with the pileus. Because of that confusion, by the Middle Ages, the cap associated with freedom and liberty was the Phrygian cap. But by that time, with Europe firmly entrenched in the feudal system, the idea of the common man being able to gain control over his own life was an fanciful thought.

During the time of the ancient Greek Empire, when a slave gained his freedom, he would wear a conical shaped cap as a sign that he had gained his freedom through legal means. The original cap used for this purpose was called a Pileus cap. It was a simple cone shaped, brimless felt cap. The slave being freed would undergo a ceremony in which he would have his head shaved and the pileus placed on his bald head. The slave would be touched on the shoulder with a rod called a vindicta, and he would henceforth be a free man. Afterward, if the freed slave did not wear the pileus cap, he ran the risk of being taken into custody and forced into slavery again. The custom became a hallmark of the ancient Roman Empire as the Roman Empire overran and assimilated the culture of the ancient Greeks. As time went on, the Phrygian cap, worn in Anatolia by the common man, became confused with the pileus. Because of that confusion, by the Middle Ages, the cap associated with freedom and liberty was the Phrygian cap. But by that time, with Europe firmly entrenched in the feudal system, the idea of the common man being able to gain control over his own life was an fanciful thought.

![]() During the latter half of the 17th Century and into the 18th, there was a renewed interest in the culture of the ‘ancients.’ Concurrent with the ‘Roman Revival’ in the arts, more and more writers urged the overthrow of oppressive monarchical governments. And as the concept that Liberty actually might be within the grasp of the common man everywhere became popular, the ‘age-old’ symbols of the strife for liberty gained renewed popularity. Despite the fact that the original pileus was long-forgotten, its spiritual godchild, the Phrygian cap again became popular.

During the latter half of the 17th Century and into the 18th, there was a renewed interest in the culture of the ‘ancients.’ Concurrent with the ‘Roman Revival’ in the arts, more and more writers urged the overthrow of oppressive monarchical governments. And as the concept that Liberty actually might be within the grasp of the common man everywhere became popular, the ‘age-old’ symbols of the strife for liberty gained renewed popularity. Despite the fact that the original pileus was long-forgotten, its spiritual godchild, the Phrygian cap again became popular.

![]() Beginning as a personal proclamation of liberty, the cap placed on top of the pole had become, over time, a public announcement of liberty and freedom.

Beginning as a personal proclamation of liberty, the cap placed on top of the pole had become, over time, a public announcement of liberty and freedom.

![]() Liberty Poles, surmounted by the Phrygian cap, were raised throughout the English colonies during the American Revolutionary War. In some instances, the pole was accompanied by the raising of ‘rebel’ flags. The first such flags tended to be traditional British flags which were altered in some way. The initial alterations consisted of the addition of the words ‘liberty’ and ‘liberty and union’ to the British Red Ensign, the standard British flag flown on all British military fortified sites. White stripes were then added to the field of red to alternate as thirteen stripes, while leaving the Union Jack occupy the canton. Later flags consisting just of the alternating thirteen red and white stripes, with the Union Jack removed from the canton, were called ‘rebel stripes.’ The flags were sometimes raised on a second pole, but more often they were attached to the Liberty Pole with its Phrygian cap on the top.

Liberty Poles, surmounted by the Phrygian cap, were raised throughout the English colonies during the American Revolutionary War. In some instances, the pole was accompanied by the raising of ‘rebel’ flags. The first such flags tended to be traditional British flags which were altered in some way. The initial alterations consisted of the addition of the words ‘liberty’ and ‘liberty and union’ to the British Red Ensign, the standard British flag flown on all British military fortified sites. White stripes were then added to the field of red to alternate as thirteen stripes, while leaving the Union Jack occupy the canton. Later flags consisting just of the alternating thirteen red and white stripes, with the Union Jack removed from the canton, were called ‘rebel stripes.’ The flags were sometimes raised on a second pole, but more often they were attached to the Liberty Pole with its Phrygian cap on the top.

![]() The French citizens, when they revolted against the House of Bourbon headed by King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette, embraced the Liberty Pole as a rallying symbol. In fact, the French people did not simply add the Phrygian cap to the Liberty Pole ~ they actually wore the cap with honor.

The French citizens, when they revolted against the House of Bourbon headed by King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette, embraced the Liberty Pole as a rallying symbol. In fact, the French people did not simply add the Phrygian cap to the Liberty Pole ~ they actually wore the cap with honor.

![]() In America, the last instance of the widespread use of the Liberty Pole to rally like-minded rebels, was during the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794. When whiskey distillers and tavern owners throughout the central and western countied of the state of Pennsylvania rebelled against the excise tax on spirits, they rallied their neighbors by raising liberty poles. One such incident took place in Bedford County at the Jean Bonnet Tavern. Liberty poles were raised as far east as Carlisle in Cumberland County. They were also raised to display solidarity in Franklin and Northumberland Counties and in Washington County in Maryland. Evidence has not been found for the raising of any Liberty Poles during the War of 1812, so the Whiskey Rebellion appears to have been the last rebellion by the common man to have used the pole as a rallying symbol.

In America, the last instance of the widespread use of the Liberty Pole to rally like-minded rebels, was during the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794. When whiskey distillers and tavern owners throughout the central and western countied of the state of Pennsylvania rebelled against the excise tax on spirits, they rallied their neighbors by raising liberty poles. One such incident took place in Bedford County at the Jean Bonnet Tavern. Liberty poles were raised as far east as Carlisle in Cumberland County. They were also raised to display solidarity in Franklin and Northumberland Counties and in Washington County in Maryland. Evidence has not been found for the raising of any Liberty Poles during the War of 1812, so the Whiskey Rebellion appears to have been the last rebellion by the common man to have used the pole as a rallying symbol.