![]() As a result of the situation it found itself in, the English army had been reduced, by the end of August, by about three thousand men. Despite the weakened constitution of his army, Cromwell made the decision to leave the environs of Edinburgh and return once again to Dunbar on the coast. Historians have speculated why Cromwell made that decision: some arguing that he resolved to return to England; some arguing that he only intended to refurbish his troops with supplies, and then to once more attempt the submission of the Scottish capital city; others speculating that he hoped to draw Leslie away from the relative security of the Edinburgh trenches for a pitched battle.

As a result of the situation it found itself in, the English army had been reduced, by the end of August, by about three thousand men. Despite the weakened constitution of his army, Cromwell made the decision to leave the environs of Edinburgh and return once again to Dunbar on the coast. Historians have speculated why Cromwell made that decision: some arguing that he resolved to return to England; some arguing that he only intended to refurbish his troops with supplies, and then to once more attempt the submission of the Scottish capital city; others speculating that he hoped to draw Leslie away from the relative security of the Edinburgh trenches for a pitched battle.

![]() In any event, on the 30th of August, the English army left Musselburgh and headed east toward Haddington. The Scots attacked the rear-guard of cavalry and caused them to go into disorder. But the English quickly recovered and the Scots backed off. About midnight, the Scots attempted an assault on the English flank positioned to the west of the town of Haddington, but were repulsed without any significant injuries. The two strikes convinced Cromwell that the Scots finally intended to engage the English in battle, and he accordingly, on the next day, the 1st of September, assembled his troops on an open field to the east of the town. After waiting a number of hours for the Scottish army to make its appearance without result, Cromwell ordered his army, which had, by that time, dwindled down to approximately twelve thousand, to proceed on toward Dunbar. The Scottish army numbered approximately twenty-seven thousand. Some observers estimated the number to be closer to thirty thousand.

In any event, on the 30th of August, the English army left Musselburgh and headed east toward Haddington. The Scots attacked the rear-guard of cavalry and caused them to go into disorder. But the English quickly recovered and the Scots backed off. About midnight, the Scots attempted an assault on the English flank positioned to the west of the town of Haddington, but were repulsed without any significant injuries. The two strikes convinced Cromwell that the Scots finally intended to engage the English in battle, and he accordingly, on the next day, the 1st of September, assembled his troops on an open field to the east of the town. After waiting a number of hours for the Scottish army to make its appearance without result, Cromwell ordered his army, which had, by that time, dwindled down to approximately twelve thousand, to proceed on toward Dunbar. The Scottish army numbered approximately twenty-seven thousand. Some observers estimated the number to be closer to thirty thousand.

![]() The English army reached Dunbar that same day, and Cromwell directed the troops to take up positions within and around the town. Brock Burn, a small stream, separated the fields to the southeast of the village from a hill by the name of Doon Hill. A couple farmhouses scattered in the region were commandeered by the English. The Scottish army, which had followed, now took up position upon the Doon Hill. Cromwell’s route to the south was effectively blocked. In addition to claiming the hill, the Scots also secured Coberspath, the only pass between Dunbar and Berwick, where the English supply ships were at anchor.

The English army reached Dunbar that same day, and Cromwell directed the troops to take up positions within and around the town. Brock Burn, a small stream, separated the fields to the southeast of the village from a hill by the name of Doon Hill. A couple farmhouses scattered in the region were commandeered by the English. The Scottish army, which had followed, now took up position upon the Doon Hill. Cromwell’s route to the south was effectively blocked. In addition to claiming the hill, the Scots also secured Coberspath, the only pass between Dunbar and Berwick, where the English supply ships were at anchor.

![]() The odds, at first, seemed to be most surely against Oliver Cromwell and the English. He was hemmed in and had perhaps three days of provisions for his men and forage for their horses. He called a council of war on 2 September, at which it was decided to make a valiant attempt against the Scots, despite the fact that they would have to scale the Doon Hill to do so. It was either that, or starve to death, or be taken captive. The attack was planned for the next day, an hour before dawn.

The odds, at first, seemed to be most surely against Oliver Cromwell and the English. He was hemmed in and had perhaps three days of provisions for his men and forage for their horses. He called a council of war on 2 September, at which it was decided to make a valiant attempt against the Scots, despite the fact that they would have to scale the Doon Hill to do so. It was either that, or starve to death, or be taken captive. The attack was planned for the next day, an hour before dawn.

![]() The situation for the English army seemed to be worse than for that of Leslie’s Scottish army. But it should be noted that the Scots had been marching for two days also. When they left Edinburgh, the Scottish soldiers likewise left the bulk of their provisions behind them. The fact of the matter was that even while they were at Edinburgh, the Scottish troops were running out of provisions. If anything, other than the difference in numbers, the two armies were fairly evenly matched in regard to either one holding any advantage over the other.

The situation for the English army seemed to be worse than for that of Leslie’s Scottish army. But it should be noted that the Scots had been marching for two days also. When they left Edinburgh, the Scottish soldiers likewise left the bulk of their provisions behind them. The fact of the matter was that even while they were at Edinburgh, the Scottish troops were running out of provisions. If anything, other than the difference in numbers, the two armies were fairly evenly matched in regard to either one holding any advantage over the other.

![]() Leslie did not want to engage the English in active combat; he preferred to starve them into defeat, but certain of his officers were for attacking the English and getting it all over with. The rank and file were restless and discouraged at the way Leslie had managed affairs for the past month. So there was continual pressure on Leslie to attack the English army. But Leslie was ready for the eminent battle. John D. Grainger noted in his book, Cromwell Against The Scots, that “Leslie was not by any means forced to fight by the clerical committee, nor even by the council of war, as rumour had it later. He chose to fight, and he was backed up in that decision by all his senior officers and by that committee. This has to be emphasised, because the influence of the ministers has been blamed for the decision. There seems to be no real evidence for this, and even Leslie did not use the excuse afterwards. He would not have left his Edinburgh lines if he had not been willing to fight at some point.”(2.33)

Leslie did not want to engage the English in active combat; he preferred to starve them into defeat, but certain of his officers were for attacking the English and getting it all over with. The rank and file were restless and discouraged at the way Leslie had managed affairs for the past month. So there was continual pressure on Leslie to attack the English army. But Leslie was ready for the eminent battle. John D. Grainger noted in his book, Cromwell Against The Scots, that “Leslie was not by any means forced to fight by the clerical committee, nor even by the council of war, as rumour had it later. He chose to fight, and he was backed up in that decision by all his senior officers and by that committee. This has to be emphasised, because the influence of the ministers has been blamed for the decision. There seems to be no real evidence for this, and even Leslie did not use the excuse afterwards. He would not have left his Edinburgh lines if he had not been willing to fight at some point.”(2.33)

![]() After his own council of war, Cromwell was in the gardens of the Earl of Roxburgh’s estate and viewing the Scots through “proƒpective glaƒses”, and to his surprise, saw Leslie’s troops descending the hill. The exhausted English soldiers would not be burdened with climbing the hill to take on the Scots after all.

After his own council of war, Cromwell was in the gardens of the Earl of Roxburgh’s estate and viewing the Scots through “proƒpective glaƒses”, and to his surprise, saw Leslie’s troops descending the hill. The exhausted English soldiers would not be burdened with climbing the hill to take on the Scots after all.

![]() The Scottish troops spent most of the 2nd and almost the entire night in repositioning themselves in the valley. During the descent down the hill, a storm broke over the Scots, drenching them entirely, including the flint match-locks of their muskets. Cromwell, in the meantime, had taken precautions to ensure that the English muskets and ammunition were kept in the dry.

The Scottish troops spent most of the 2nd and almost the entire night in repositioning themselves in the valley. During the descent down the hill, a storm broke over the Scots, drenching them entirely, including the flint match-locks of their muskets. Cromwell, in the meantime, had taken precautions to ensure that the English muskets and ammunition were kept in the dry.

![]() The Scots took up a formation of cavalry flanking either side of the foot soldiers, a standard battle formation, stretching from a space between the base of Doon Hill and Brock Burn to the road from Dunbar to Berwick. Cromwell likewise formed his regiments on the northwest side of the burn.

The Scots took up a formation of cavalry flanking either side of the foot soldiers, a standard battle formation, stretching from a space between the base of Doon Hill and Brock Burn to the road from Dunbar to Berwick. Cromwell likewise formed his regiments on the northwest side of the burn.

![]() Cromwell planned to attack the Scots early on the following morning, Tuesday, 3 September, hoping to catch them off guard as they would be tired from the descent from Doon Hill. The attack would begin with an assault by the center flank. After dusk on the night of the 2nd, the English right flank of cavalry had been shifted to take position in the center, and some of the infantry then shifted to form the new right flank along with the artillery. The vanguard of the English center flank was now comprised of six regiments of cavalry under Major-General John Lambert, along with three and a half regiments of foot soldiers under the command of George Monck. Behind them were Pride’s brigade of one and a half regiments of foot soldiers and the Lord-General Cromwell’s own cavalry regiment and the dragoons.

Cromwell planned to attack the Scots early on the following morning, Tuesday, 3 September, hoping to catch them off guard as they would be tired from the descent from Doon Hill. The attack would begin with an assault by the center flank. After dusk on the night of the 2nd, the English right flank of cavalry had been shifted to take position in the center, and some of the infantry then shifted to form the new right flank along with the artillery. The vanguard of the English center flank was now comprised of six regiments of cavalry under Major-General John Lambert, along with three and a half regiments of foot soldiers under the command of George Monck. Behind them were Pride’s brigade of one and a half regiments of foot soldiers and the Lord-General Cromwell’s own cavalry regiment and the dragoons.

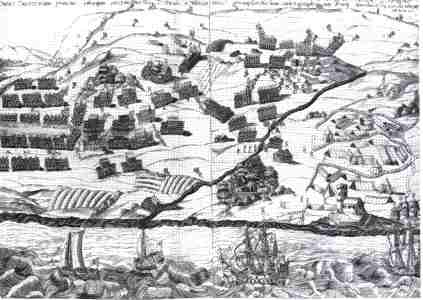

The Battle of Dunbar ~ Source unknown.

![]() The thrust of the attack was to be against the Scottish center flank positioned on the level ground over which the road passed. The Scots’ left flank, which was comprised of a third of the Scottish cavalry and some of the infantry, and was crowded into a narrow space between the ravine of Brock Burn and the foot of Doon Hill, could be kept isolated and impotent by the English artillery which had been placed directly opposite on the northwest side of the burn.

The thrust of the attack was to be against the Scottish center flank positioned on the level ground over which the road passed. The Scots’ left flank, which was comprised of a third of the Scottish cavalry and some of the infantry, and was crowded into a narrow space between the ravine of Brock Burn and the foot of Doon Hill, could be kept isolated and impotent by the English artillery which had been placed directly opposite on the northwest side of the burn.

![]() About 4:30 on the morning of the 3rd of September, the attack got underway, with three regiments of cavalry under commanders Lambert, Lilburne and Whalley crossing the burn and assailing the Scots positioned on the road. At just about the same time, the English guns began a bombardment of the Scottish left flank. Because of the intensity of the rainstorm that night, the Scots probably had not figured on the English attacking until they dried out a bit. The assault caught the Scots off-guard; they were pushed a short distance backward. The Scottish cavalry quickly mounted and delivered a strong counter-attack to the English, in turn pushing Lambert’s regiments back to the burn. The main fighting, to this point, was concentrated between a farm, Broxmouth House and the mouth of the ravine that began just to the south of the road.

About 4:30 on the morning of the 3rd of September, the attack got underway, with three regiments of cavalry under commanders Lambert, Lilburne and Whalley crossing the burn and assailing the Scots positioned on the road. At just about the same time, the English guns began a bombardment of the Scottish left flank. Because of the intensity of the rainstorm that night, the Scots probably had not figured on the English attacking until they dried out a bit. The assault caught the Scots off-guard; they were pushed a short distance backward. The Scottish cavalry quickly mounted and delivered a strong counter-attack to the English, in turn pushing Lambert’s regiments back to the burn. The main fighting, to this point, was concentrated between a farm, Broxmouth House and the mouth of the ravine that began just to the south of the road.

![]() Leslie became over confident that his army was gaining the upper hand when Lambert’s regiments were pushed backward. He did not realize fully that his entire left flank and much of the center and right were being held down by the English cannon bombardment. Following the initial assault, the entire English army advanced on the Scots. Cromwell led the troops he had held in reserve, consisting of Pride’s brigade of three foot regiments, the dragoons and his own cavalry regiment, around the Broxmouth House and across the burn at what was known as the ‘lower crossing’ which was located between the house and the sea coast. The reserve regiments rushed upon the English right flank with a shout. Lambert’s men, hearing the shout go up, got their second wind of courage, halted their retreat, and poured renewed strength into counter-attacking the Scot’s counterattack. Suddenly the tide was turned back against Leslie. In the confused turmoil that erupted, the Scottish cavalry broke and fled, some riding south toward Berwick, others up over Doon Hill and back around to Haddington. The loss of the cavalry resulted in the end for the foot regiments. Cromwell’s English cavalry charged into Leslie’s infantry lines, slaughtering them unmercifully. According to some accounts, the fight was hot and heavy, lasting only about one hour. It was proudly said that two regiments of the Scots, Campbell of Lawer’s Highlanders and Sir John Holden of Gleneggies’ regiment, bravely stood their ground, but were practically all killed in the fight.

Leslie became over confident that his army was gaining the upper hand when Lambert’s regiments were pushed backward. He did not realize fully that his entire left flank and much of the center and right were being held down by the English cannon bombardment. Following the initial assault, the entire English army advanced on the Scots. Cromwell led the troops he had held in reserve, consisting of Pride’s brigade of three foot regiments, the dragoons and his own cavalry regiment, around the Broxmouth House and across the burn at what was known as the ‘lower crossing’ which was located between the house and the sea coast. The reserve regiments rushed upon the English right flank with a shout. Lambert’s men, hearing the shout go up, got their second wind of courage, halted their retreat, and poured renewed strength into counter-attacking the Scot’s counterattack. Suddenly the tide was turned back against Leslie. In the confused turmoil that erupted, the Scottish cavalry broke and fled, some riding south toward Berwick, others up over Doon Hill and back around to Haddington. The loss of the cavalry resulted in the end for the foot regiments. Cromwell’s English cavalry charged into Leslie’s infantry lines, slaughtering them unmercifully. According to some accounts, the fight was hot and heavy, lasting only about one hour. It was proudly said that two regiments of the Scots, Campbell of Lawer’s Highlanders and Sir John Holden of Gleneggies’ regiment, bravely stood their ground, but were practically all killed in the fight.

![]() In the end, the entire Scottish army was routed; it retreated toward Haddington with the English in hot pursuit. Nearly four thousand Scots were slain on the battlefield and in the retreat to Haddington and Edinburgh. Leslie escaped to Edinburgh, the garrison of which, upon receiving the news of the disaster, made preparations to leave the city.

In the end, the entire Scottish army was routed; it retreated toward Haddington with the English in hot pursuit. Nearly four thousand Scots were slain on the battlefield and in the retreat to Haddington and Edinburgh. Leslie escaped to Edinburgh, the garrison of which, upon receiving the news of the disaster, made preparations to leave the city.

![]() Some ten thousand Scots were taken prisoner at Dunbar. They included such notables: Sir James Lumsdale, the Lieutenant-General of the foot regiments; Lord Libberton; adjutant-general Bickerton; Scout-Master Campbell; Sir William Douglass; Lord Grandison; and Colonel Gourdon. There were twelve lieutenant-colonels, six majors, forty-two captains and seventy-five lieutenants taken captive. It has been estimated that nearly fifteen thousand arms and all the artillery and ammunition became the prize of the English. And to cap it all off, nearly two hundred regimental colours were taken and later hung in Westminster Hall as trophies.

Some ten thousand Scots were taken prisoner at Dunbar. They included such notables: Sir James Lumsdale, the Lieutenant-General of the foot regiments; Lord Libberton; adjutant-general Bickerton; Scout-Master Campbell; Sir William Douglass; Lord Grandison; and Colonel Gourdon. There were twelve lieutenant-colonels, six majors, forty-two captains and seventy-five lieutenants taken captive. It has been estimated that nearly fifteen thousand arms and all the artillery and ammunition became the prize of the English. And to cap it all off, nearly two hundred regimental colours were taken and later hung in Westminster Hall as trophies.

![]() On the English side, only three hundred lost their lives. The Battle of Dunbar would become known as one of Oliver Cromwell’s crowning achievements. He entered Edinburgh on 7 September 1650.

On the English side, only three hundred lost their lives. The Battle of Dunbar would become known as one of Oliver Cromwell’s crowning achievements. He entered Edinburgh on 7 September 1650.

![]() General Leslie was able to muster about four thousand cavalry troops after the battle of Dunbar. With those troops he left Edinburgh and headed to Stirling. Apart from Governor Sir Walter Dundas and a number of Presbyterian Ministers who had taken refuge in Edinburgh Castle when the news first arrived of the defeat at Dunbar (the Castle’s defenders would surrender on 24 December), the majority of the members of the clergy and the Kirk, who were still in the city, went along with Leslie to take up temporary residence in Stirling Castle. An inquest into the cause of the disastrous defeat of Leslie’s army was begun almost immediately. He argued that the majority of the blame lay on the negligence of the officers and the laziness of the rank and file. To his credit, though, Leslie admitted that he had to share in the blame, and offered his resignation to the general assembly. But there was no one as qualified as him to take the position, and so Leslie’s resignation was denied.

General Leslie was able to muster about four thousand cavalry troops after the battle of Dunbar. With those troops he left Edinburgh and headed to Stirling. Apart from Governor Sir Walter Dundas and a number of Presbyterian Ministers who had taken refuge in Edinburgh Castle when the news first arrived of the defeat at Dunbar (the Castle’s defenders would surrender on 24 December), the majority of the members of the clergy and the Kirk, who were still in the city, went along with Leslie to take up temporary residence in Stirling Castle. An inquest into the cause of the disastrous defeat of Leslie’s army was begun almost immediately. He argued that the majority of the blame lay on the negligence of the officers and the laziness of the rank and file. To his credit, though, Leslie admitted that he had to share in the blame, and offered his resignation to the general assembly. But there was no one as qualified as him to take the position, and so Leslie’s resignation was denied.

2.33 Cromwell Against The Scots: The Last Anglo-Scottish War 1650-1652, by John D. Grainger,1997, pp 42-43.