![]() While Cromwell was away from London, his son-in-law, Henry Ireton, attempted to keep the Parliament and the military unified. But in Cromwell’s absence, the pro-Presbyterian contingent, which Cromwell had ousted when he had Denzil Holles and his supporters removed a year earlier, had begun to once more occupy seats in the Assembly. One of the things they did was to pass an act which repealed the Vote Of No Addresses, and in September began to hold new negotiations with the King. This angered the rank and file of the army, who wanted the King to pay for the blood he had caused to be shed.

While Cromwell was away from London, his son-in-law, Henry Ireton, attempted to keep the Parliament and the military unified. But in Cromwell’s absence, the pro-Presbyterian contingent, which Cromwell had ousted when he had Denzil Holles and his supporters removed a year earlier, had begun to once more occupy seats in the Assembly. One of the things they did was to pass an act which repealed the Vote Of No Addresses, and in September began to hold new negotiations with the King. This angered the rank and file of the army, who wanted the King to pay for the blood he had caused to be shed.

![]() Under Ireton’s direction, on 8 December, 1648, a contingent of the army led by Colonel Thomas Pride barred the doors of the Parliament and expelled approximately one hundred and forty members who were considered to be sympathetic to Charles. The incident, known as Pride’s Purge left only some fifty members of the House of Commons, later to be called the Rump Parliament. Cromwell arrived back at London on the night of Pride’s Purge. Although not having been the instigator of the army’s actions, he gave his approval of those actions, but insisted that Charles simply be removed from the Throne and another named to the monarchy. The army leaders, urged on by Ireton, wanted the King to stand trial and be punished. Even as late as Christmas Day, according to a contemporary newspaper report, Oliver Cromwell was still in opposition to executing the King, as other members of the Parliament were advocating. But in the opening days of January, 1649 speaking before the House of Commons, Cromwell stated that he felt anyone who ‘carried on a design’ to depose or execute the King was a traitor, but that “since the Providence of God hath cast this upon us, I cannot but submit to Providence.”

Under Ireton’s direction, on 8 December, 1648, a contingent of the army led by Colonel Thomas Pride barred the doors of the Parliament and expelled approximately one hundred and forty members who were considered to be sympathetic to Charles. The incident, known as Pride’s Purge left only some fifty members of the House of Commons, later to be called the Rump Parliament. Cromwell arrived back at London on the night of Pride’s Purge. Although not having been the instigator of the army’s actions, he gave his approval of those actions, but insisted that Charles simply be removed from the Throne and another named to the monarchy. The army leaders, urged on by Ireton, wanted the King to stand trial and be punished. Even as late as Christmas Day, according to a contemporary newspaper report, Oliver Cromwell was still in opposition to executing the King, as other members of the Parliament were advocating. But in the opening days of January, 1649 speaking before the House of Commons, Cromwell stated that he felt anyone who ‘carried on a design’ to depose or execute the King was a traitor, but that “since the Providence of God hath cast this upon us, I cannot but submit to Providence.”

![]() The Parliament established a High Court Of Justice consisting of one hundred and thirty-five members of the Parliament, army officers and citizens. About fifty of those named to the court refused to participate in it. King Charles was brought to St. James to await the trial. During that time, the Scottish Parliament send a group of commissioners to protest against the trial.

The Parliament established a High Court Of Justice consisting of one hundred and thirty-five members of the Parliament, army officers and citizens. About fifty of those named to the court refused to participate in it. King Charles was brought to St. James to await the trial. During that time, the Scottish Parliament send a group of commissioners to protest against the trial.

![]() The trial against the King commenced on Saturday, the 20th of January, 1649. The charge brought up against him was:(2.17)

The trial against the King commenced on Saturday, the 20th of January, 1649. The charge brought up against him was:(2.17)

| “That he had endeavour’d to set up a tyrannical power, and to that end had rais’d and maintain’d in the land a cruel war against the parliament; whereby the country had been miserably wasted, the publick treasure exhausted, thousands of people had lost their lives, and innumerable other mischiefs committed..” |

![]() The King was asked to enter a plea, but he refused to plead either guilty or not guilty. He was brought again to the court on Monday, the 22nd, but he refused again to enter a plea. He did the same thing on the following day. On the 27th of January, the King desired to be heard before both houses of the parliament in the ‘painted chamber’. It was believed that he planned to resign his crown to his son, the Prince of Wales, and the judges of the court would not grant his wish. Instead, they again asked him to enter a plea, to which he once more refused. Upon his refusal this time, John Bradshaw, the President of the Commission for the trial of the King, stated that his request to an audience with the parliament was intended simply to delay the proceedings, and that if he had no more to say at this time, the judgement would proceed. The King answered that he had no more to say at this time. Bradshaw therefore read the sentence:(2.18)

The King was asked to enter a plea, but he refused to plead either guilty or not guilty. He was brought again to the court on Monday, the 22nd, but he refused again to enter a plea. He did the same thing on the following day. On the 27th of January, the King desired to be heard before both houses of the parliament in the ‘painted chamber’. It was believed that he planned to resign his crown to his son, the Prince of Wales, and the judges of the court would not grant his wish. Instead, they again asked him to enter a plea, to which he once more refused. Upon his refusal this time, John Bradshaw, the President of the Commission for the trial of the King, stated that his request to an audience with the parliament was intended simply to delay the proceedings, and that if he had no more to say at this time, the judgement would proceed. The King answered that he had no more to say at this time. Bradshaw therefore read the sentence:(2.18)

| “For all which treasons and crimes, this court doth adjudge, that the said Charles Stuart, as a tyrant, traitor, murderer, and publick enemy, shall be put to death, by the severing his head from his body.” |

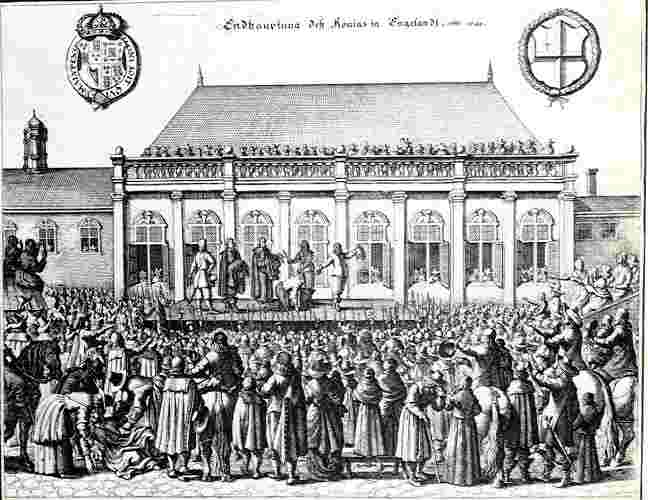

![]() On 30 January, 1649, at about ten o’clock in the morning, the King was led to a scaffold in the courtyard of White-hall. He kneeled down and placed his head on the block, and with a single blow, the executioner severed his head from his body. In the blink of an eye, Charles Stuart was transformed from a tyrant into a martyr.

On 30 January, 1649, at about ten o’clock in the morning, the King was led to a scaffold in the courtyard of White-hall. He kneeled down and placed his head on the block, and with a single blow, the executioner severed his head from his body. In the blink of an eye, Charles Stuart was transformed from a tyrant into a martyr.

King Charles I is executed. ~ Source unknown.

![]() The monarchy and the House of Lords were formally abolished by March of 1649. The Rump Parliament passed a law in May which declared the kingdom at an end; in its stead was created the English Commonwealth. It consisted of a single chamber of the legislature and the Council of State, the executive branch. As the Council of State consisted of forty-some members, any matters to be investigated would be taken up by smaller ad hoc committees.

The monarchy and the House of Lords were formally abolished by March of 1649. The Rump Parliament passed a law in May which declared the kingdom at an end; in its stead was created the English Commonwealth. It consisted of a single chamber of the legislature and the Council of State, the executive branch. As the Council of State consisted of forty-some members, any matters to be investigated would be taken up by smaller ad hoc committees.

![]() The Scottish people were horrified that the English had put Charles Stuart to death. Even though Charles had been the English king, he was also the Scottish king, and many of those in Scotland wondered by what right the English could take the life of their mutual king without Scottish consent. Not only had the execution of Charles Stuart deprived the Scots of their king, but the Pride’s Purge had removed from the English Parliament all of the English Presbyterians, the true allies of the Scottish Covenanters. It could be said that the ax which severed the head from Charles Stuart’s body severed the ties between Scotland and England.

The Scottish people were horrified that the English had put Charles Stuart to death. Even though Charles had been the English king, he was also the Scottish king, and many of those in Scotland wondered by what right the English could take the life of their mutual king without Scottish consent. Not only had the execution of Charles Stuart deprived the Scots of their king, but the Pride’s Purge had removed from the English Parliament all of the English Presbyterians, the true allies of the Scottish Covenanters. It could be said that the ax which severed the head from Charles Stuart’s body severed the ties between Scotland and England.

2.17 The Life Of Oliver Cromwell, Lord-Protector Of The Commonwealth Of England, Scotland, And Ireland, by J. Brotherton 1755, p 102.

2.18 ibid., p 103.