![]() The ‘Church’ in England, at the beginning of the Seventeenth Century, was actually the Anglican (i.e. the English) Church, a branch of the Roman Catholic Church, but a branch that had broken off nearly a century earlier. The Anglican Church can trace its roots back to the 500s. In the Sixth Century, St. Augustine had been sent to Britain to bring about a more orthodox, or Apostolic, succession in the Celtic Christian church that had evolved there through the efforts of missionaries. St. Augustine’s interference only partly succeeded; the Celtic influence was too great to be overcome easily. During the next eleven centuries, the Anglican Church continued to evolve; it accepted much of the ritual of the Roman Catholic church, but also retained certain of its Celtic customs. There also evolved a series of disagreements with the degree of authority the Pope should possess over the affairs of the Anglican Church. Finally, in 1529, the long series of disagreements with the Papal authority came to a head, when King Henry VIII, in anger over the fact that the Pope refused to annul his marriage to Catherine (who could not provide him with a male heir), declared that he did not require the Pope’s permission any longer.

The ‘Church’ in England, at the beginning of the Seventeenth Century, was actually the Anglican (i.e. the English) Church, a branch of the Roman Catholic Church, but a branch that had broken off nearly a century earlier. The Anglican Church can trace its roots back to the 500s. In the Sixth Century, St. Augustine had been sent to Britain to bring about a more orthodox, or Apostolic, succession in the Celtic Christian church that had evolved there through the efforts of missionaries. St. Augustine’s interference only partly succeeded; the Celtic influence was too great to be overcome easily. During the next eleven centuries, the Anglican Church continued to evolve; it accepted much of the ritual of the Roman Catholic church, but also retained certain of its Celtic customs. There also evolved a series of disagreements with the degree of authority the Pope should possess over the affairs of the Anglican Church. Finally, in 1529, the long series of disagreements with the Papal authority came to a head, when King Henry VIII, in anger over the fact that the Pope refused to annul his marriage to Catherine (who could not provide him with a male heir), declared that he did not require the Pope’s permission any longer.

![]() During the years leading into the Seventeenth Century, the spiritual needs of the majority of the people of Scotland were served by a number of faiths, primarily Catholic, but also including some of the new Protestant sects, such as Calvinistic Presbyterianism. Although not thought of as the ‘official’ religion, there was no denying that the Catholic Church wielded tremendous power. The Church owned large tracts of land and as such, controlled much of the wealth of the country. But the Protestant sects were gaining followers throughout the country, as the result of the Reformation that was spreading throughout Europe and into the Isles.

During the years leading into the Seventeenth Century, the spiritual needs of the majority of the people of Scotland were served by a number of faiths, primarily Catholic, but also including some of the new Protestant sects, such as Calvinistic Presbyterianism. Although not thought of as the ‘official’ religion, there was no denying that the Catholic Church wielded tremendous power. The Church owned large tracts of land and as such, controlled much of the wealth of the country. But the Protestant sects were gaining followers throughout the country, as the result of the Reformation that was spreading throughout Europe and into the Isles.

![]() By the time Charles inherited the throne (1625), a Book of Common Prayer had been introduced in England (1549), and the books of the Bible had been codified and formally translated by a group of scholars under the direction of Charles’ father, King James (1611).

By the time Charles inherited the throne (1625), a Book of Common Prayer had been introduced in England (1549), and the books of the Bible had been codified and formally translated by a group of scholars under the direction of Charles’ father, King James (1611).

![]() Also by the time Charles took his place on the throne, a new group of Protestants had emerged in England: the Puritans. Growing out of Calvanist theory as advocated by the theologian John Knox, the Puritans comprised a dour, serious sect who aimed to remove all ceremony from the church service that was not specifically noted in the Bible. It should be remembered that much of the ritual and dogma of Catholicism was established by early leaders of the Christian movement, and were not even mentioned by Christ and his disciples and apostles. The Puritans proposed abolishing many of the roles of the bishops in the Church, and replacing the episcopate (i.e. relating to the heirarchy of bishops in which successively higher ranking officials govern those below) with a presbyterian (i.e. relating to a collection of ministers of equal ranking) form of structure.

Also by the time Charles took his place on the throne, a new group of Protestants had emerged in England: the Puritans. Growing out of Calvanist theory as advocated by the theologian John Knox, the Puritans comprised a dour, serious sect who aimed to remove all ceremony from the church service that was not specifically noted in the Bible. It should be remembered that much of the ritual and dogma of Catholicism was established by early leaders of the Christian movement, and were not even mentioned by Christ and his disciples and apostles. The Puritans proposed abolishing many of the roles of the bishops in the Church, and replacing the episcopate (i.e. relating to the heirarchy of bishops in which successively higher ranking officials govern those below) with a presbyterian (i.e. relating to a collection of ministers of equal ranking) form of structure.

![]() Charles came to the throne at a time when the Roman Catholic trappings of the Anglican Church was being questioned by many of the common citizens in both England and Scotland. The religious environment was not the most favorable one in which to attempt to thrust the Anglican Church down the throats of the people. But Charles had been away from Scotland all of his life, and knew practically nothing of the widespread support for the Presbyterian faith. So what did he do? He started his reign by issuing the Act of Revocation in 1625, which restored to the Church the lands and tithes that had been distributed to the nobles during the Reformation. He demanded, in 1629, that the religious practice in Scotland was to conform to the English model. He then chose to hold his coronation in St. Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh in 1633. He was well on his way to becoming very unpopular with almost every faction in Scotland. The finale came in 1637 with the publishing of the Revised Prayer Book for Scotland.

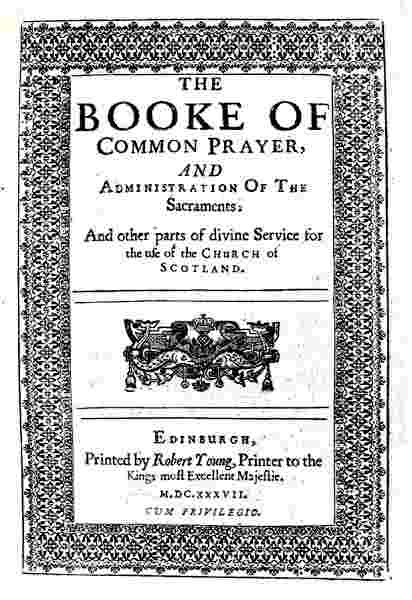

Charles came to the throne at a time when the Roman Catholic trappings of the Anglican Church was being questioned by many of the common citizens in both England and Scotland. The religious environment was not the most favorable one in which to attempt to thrust the Anglican Church down the throats of the people. But Charles had been away from Scotland all of his life, and knew practically nothing of the widespread support for the Presbyterian faith. So what did he do? He started his reign by issuing the Act of Revocation in 1625, which restored to the Church the lands and tithes that had been distributed to the nobles during the Reformation. He demanded, in 1629, that the religious practice in Scotland was to conform to the English model. He then chose to hold his coronation in St. Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh in 1633. He was well on his way to becoming very unpopular with almost every faction in Scotland. The finale came in 1637 with the publishing of the Revised Prayer Book for Scotland.

The Revised Book of Common Prayer, published in 1637 ~ Source unknown.

![]() The Prayer Book was read for the first time on 23 July, 1637 at St. Giles Cathedral. Its initial reading caused a riot, in which, it was said, the ladies in attendance played a leading part. The Privy Council, fearing for their lives, went into seculsion in Holyroodhouse. The opposition to the new Prayer Book raised to such a fever pitch that certain bishops had to resort to extreme measures to ensure their own safety. It was said that the Bishop of Brechin conducted his services with a pair of loaded pistols laid in front of him.

The Prayer Book was read for the first time on 23 July, 1637 at St. Giles Cathedral. Its initial reading caused a riot, in which, it was said, the ladies in attendance played a leading part. The Privy Council, fearing for their lives, went into seculsion in Holyroodhouse. The opposition to the new Prayer Book raised to such a fever pitch that certain bishops had to resort to extreme measures to ensure their own safety. It was said that the Bishop of Brechin conducted his services with a pair of loaded pistols laid in front of him.