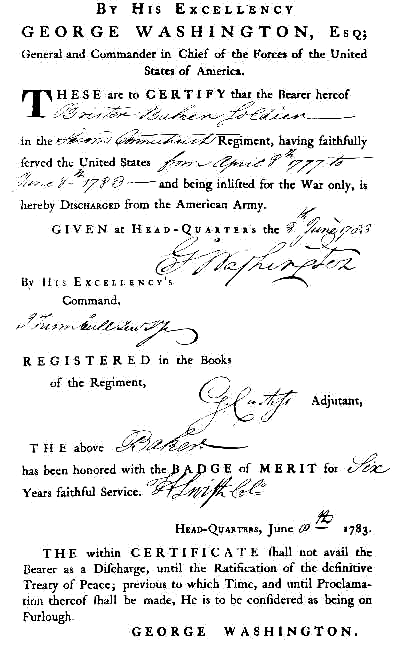

![]() According to the discharge certificate shown above, a man by the name of Brister Baker served for six years in the Second Connecticut Regiment of the Continental Line - from 08 April 1777 to 08 June 1783.

According to the discharge certificate shown above, a man by the name of Brister Baker served for six years in the Second Connecticut Regiment of the Continental Line - from 08 April 1777 to 08 June 1783.

![]() This discharge certificate is not very different from any other discharge which was issued during the American Revolutionary War. From the looks of it, Brister Baker was just another soldier who had enlisted for the duration of the war, and ended up spending six years in the Second Connecticut Regiment of the Continental Line.

This discharge certificate is not very different from any other discharge which was issued during the American Revolutionary War. From the looks of it, Brister Baker was just another soldier who had enlisted for the duration of the war, and ended up spending six years in the Second Connecticut Regiment of the Continental Line.

![]() The thing that the discharge paper does not reveal is the fact that Brister Baker was a black man. The lack of visibility of Patriot Bakers skin color on the discharge paper emphasizes the lack of visibility that history has generally afforded the blacks who served as Patriots during the American Revolutionary War.

The thing that the discharge paper does not reveal is the fact that Brister Baker was a black man. The lack of visibility of Patriot Bakers skin color on the discharge paper emphasizes the lack of visibility that history has generally afforded the blacks who served as Patriots during the American Revolutionary War.

![]() Although it comes as a surprise to most people when they initially hear it, the first colonial to die at the hands of the British was a man of African descent.

Although it comes as a surprise to most people when they initially hear it, the first colonial to die at the hands of the British was a man of African descent.

![]() In Boston, where British troops had been quartered since 1768, open quarreling had broken out at various times, but nothing of any serious consequence came of these clashes. On Friday, 02 March, 1770 a fist fight broke out between a town laborer and a soldier in the afternoon and developed into a small riot. By evening, bands of civilians and soldiers itching for a fight were roaming the streets, but the growing rabble was quieted down by the soldiers and other townspeople who were mindful of the approaching Sabbath, which the God-fearing New Englanders respected. Things were quiet until the following week began.

In Boston, where British troops had been quartered since 1768, open quarreling had broken out at various times, but nothing of any serious consequence came of these clashes. On Friday, 02 March, 1770 a fist fight broke out between a town laborer and a soldier in the afternoon and developed into a small riot. By evening, bands of civilians and soldiers itching for a fight were roaming the streets, but the growing rabble was quieted down by the soldiers and other townspeople who were mindful of the approaching Sabbath, which the God-fearing New Englanders respected. Things were quiet until the following week began.

![]() According to one tradition, on Monday, 05 March, five youths, passing through a narrow alley, came upon three soldiers striking their broadswords against a (brick or stone) wall for the sport of watching the sparks fly. One of the youths called out to the others to avoid the soldiers, and all of a sudden one of the soldiers quickly turned around and struck him on the arm with his sword. The youths returned blows and a squabble ensued. The soldiers escaped into their barracks and recruited between twelve and twenty others to follow them back to teach the boys a lesson. With their cutlasses and muskets in hand the band of soldiers swept through the streets striking and bullying any civilians they met. Some of the townsfolk returned blows and pelted the soldiers with snowballs and shots were fired into the crowds of civilians.

According to one tradition, on Monday, 05 March, five youths, passing through a narrow alley, came upon three soldiers striking their broadswords against a (brick or stone) wall for the sport of watching the sparks fly. One of the youths called out to the others to avoid the soldiers, and all of a sudden one of the soldiers quickly turned around and struck him on the arm with his sword. The youths returned blows and a squabble ensued. The soldiers escaped into their barracks and recruited between twelve and twenty others to follow them back to teach the boys a lesson. With their cutlasses and muskets in hand the band of soldiers swept through the streets striking and bullying any civilians they met. Some of the townsfolk returned blows and pelted the soldiers with snowballs and shots were fired into the crowds of civilians.

![]() According to another tradition, on the evening of Monday, 05 March, between the hours of six and seven o'clock, a crowd of upwards of seven hundred, carrying clubs and other weapons, assembled in King Street. The crowd was shouting, "Let us drive out these rascals! They have no business here - drive them out!" By nine o'clock the crowd had increased in both size and fervor, and an attack was made on some British soldiers in Dock Square. The crowd began to riot and destroy throughout the town. Around midnight, a couple of the town's leading citizens attempted to bring order to the rabble, and had almost succeeded when a man began to cry out to the people, "To the main guard! To the main guard!" The crowd quickly took up the cry and headed toward the section of the town in which the main body of British troops were being quartered. As the crowd passed the custom-house, a boy pointed to the sentinel on duty and cried out, "That's the scoundrel who knocked me down." As the mob surged toward the sentinel, he tried to load his musket, but was overwhelmed. The mob was pelting him with snowballs and pieces of ice, so the sentinel ran up to the custom-house door and attempted to enter the building. The door could not be opened, and the beseiged guard called out to his fellows for assistance. The officer on hand was Captain Preston, who quickly dispatched eight men to the sentinel's aid. The crowd turned their attention on the newly arrived guard and began to pelt them with whatever they could find. A mulatto, by the name of Crispus Attucks, was with a group of sailors nearest to the guard who were loading their muskets. He dared them to fire, but the soldiers were trained not to fire unless under the order of their captain. The crowd pressed forward against the soldiers, taunting them to fire. Attucks and the sailors struck the soldiers' muskets with sticks and clubs all the while deriding the soldiers with taunts of "Come on! Don't be afraid of 'em - they daren't fire! Knock 'em over! Kill 'em!" Just then Captain Preston moved to get between the angry mob and his soldiers. Attucks struck at Preston's head, but the British captain deflected the blow with his arm. In the process, though, he knocked the musket out of the hands of one of the soldiers, a man by the name of Montgomery, and it fell to the ground near Attucks. Attucks grabbed up the musket as Montgomery struggled to retain possession of it. At about the same time, voices in the crowd were shouting to Preston, "Why don't you fire?" Montgomery, hearing the shouting, and being energized by the sound of it, got the gun away from Attucks and, as he rose up from where he and the mulatto had been struggling, he fired the musket, killing Attucks instantly. No sooner had Montgomery fired his musket, than five of the other soldiers fired their own muskets into the crowd.

According to another tradition, on the evening of Monday, 05 March, between the hours of six and seven o'clock, a crowd of upwards of seven hundred, carrying clubs and other weapons, assembled in King Street. The crowd was shouting, "Let us drive out these rascals! They have no business here - drive them out!" By nine o'clock the crowd had increased in both size and fervor, and an attack was made on some British soldiers in Dock Square. The crowd began to riot and destroy throughout the town. Around midnight, a couple of the town's leading citizens attempted to bring order to the rabble, and had almost succeeded when a man began to cry out to the people, "To the main guard! To the main guard!" The crowd quickly took up the cry and headed toward the section of the town in which the main body of British troops were being quartered. As the crowd passed the custom-house, a boy pointed to the sentinel on duty and cried out, "That's the scoundrel who knocked me down." As the mob surged toward the sentinel, he tried to load his musket, but was overwhelmed. The mob was pelting him with snowballs and pieces of ice, so the sentinel ran up to the custom-house door and attempted to enter the building. The door could not be opened, and the beseiged guard called out to his fellows for assistance. The officer on hand was Captain Preston, who quickly dispatched eight men to the sentinel's aid. The crowd turned their attention on the newly arrived guard and began to pelt them with whatever they could find. A mulatto, by the name of Crispus Attucks, was with a group of sailors nearest to the guard who were loading their muskets. He dared them to fire, but the soldiers were trained not to fire unless under the order of their captain. The crowd pressed forward against the soldiers, taunting them to fire. Attucks and the sailors struck the soldiers' muskets with sticks and clubs all the while deriding the soldiers with taunts of "Come on! Don't be afraid of 'em - they daren't fire! Knock 'em over! Kill 'em!" Just then Captain Preston moved to get between the angry mob and his soldiers. Attucks struck at Preston's head, but the British captain deflected the blow with his arm. In the process, though, he knocked the musket out of the hands of one of the soldiers, a man by the name of Montgomery, and it fell to the ground near Attucks. Attucks grabbed up the musket as Montgomery struggled to retain possession of it. At about the same time, voices in the crowd were shouting to Preston, "Why don't you fire?" Montgomery, hearing the shouting, and being energized by the sound of it, got the gun away from Attucks and, as he rose up from where he and the mulatto had been struggling, he fired the musket, killing Attucks instantly. No sooner had Montgomery fired his musket, than five of the other soldiers fired their own muskets into the crowd.

![]() Irregardless of which version of the story is factual, three civilians were killed outright and two were mortally wounded. The three killed included Crispus Attucks, Samuel Gray and James Caldwell. Samuel Maverick received a wound from which he died the following morning, and Patrick Carr received a mortal wound which claimed his life a week later.

Irregardless of which version of the story is factual, three civilians were killed outright and two were mortally wounded. The three killed included Crispus Attucks, Samuel Gray and James Caldwell. Samuel Maverick received a wound from which he died the following morning, and Patrick Carr received a mortal wound which claimed his life a week later.

![]() Contemporary accounts described Crispus Attucks as a mulatto. The term mulatto did not, in the 1770s, denote a mixture of white and black genetics. It simply referred to the color of the mans skin as being lighter than others.

Contemporary accounts described Crispus Attucks as a mulatto. The term mulatto did not, in the 1770s, denote a mixture of white and black genetics. It simply referred to the color of the mans skin as being lighter than others.

![]() Although there were some free blacks in the colonies at the time, such as Crispus Attucks, most people of African descent were slaves to the white Euro-Americans. At the outbreak of hostilities the population of the colonies was between 2,500,000 and 3,000,000, of which it is believed that between 500,000 and 600,000, or between fifteen and twenty percent, were black. Assuming that a quarter of that number were men of age to serve, there would have been almost 150,000 men available for service in the American armies.

Although there were some free blacks in the colonies at the time, such as Crispus Attucks, most people of African descent were slaves to the white Euro-Americans. At the outbreak of hostilities the population of the colonies was between 2,500,000 and 3,000,000, of which it is believed that between 500,000 and 600,000, or between fifteen and twenty percent, were black. Assuming that a quarter of that number were men of age to serve, there would have been almost 150,000 men available for service in the American armies.

![]() [Note: The discussion which follows refers to the utilization of black men in the ranks of the Continental Army as compensated soldiers, rather than in the militia or in the duty of service troops whose sole purpose was in building defences.]

[Note: The discussion which follows refers to the utilization of black men in the ranks of the Continental Army as compensated soldiers, rather than in the militia or in the duty of service troops whose sole purpose was in building defences.]

![]() One of the practices of the military system was the substitution practice. A man was permitted to send a male servant, usually a black slave, but sometimes a white indentured servant, to serve in his place. This practice resulted in a number of black men serving in the army despite the fact that there was no provision for them to be enlisted.

One of the practices of the military system was the substitution practice. A man was permitted to send a male servant, usually a black slave, but sometimes a white indentured servant, to serve in his place. This practice resulted in a number of black men serving in the army despite the fact that there was no provision for them to be enlisted.

![]() The large pool of available soldiers was not tapped effectively, though. One of the possible reasons for their not being utilized was the fact that most of the black men were slaves, and every colony permitted the institution of slavery. The Continental Congress, composed mainly of wealthy landholders, many of whom were slave owners themselves, were not inclined to enlist a black man, and in so doing deprive the slave owner of his servant. As a sidenote to this, it might be noted that Thomas Jefferson, in the preliminary draft of the Declaration of Independence, had included a scathing comment on George III as continuing to promote the slave trade. According to Jefferson, in a letter years later, the passage had been

The large pool of available soldiers was not tapped effectively, though. One of the possible reasons for their not being utilized was the fact that most of the black men were slaves, and every colony permitted the institution of slavery. The Continental Congress, composed mainly of wealthy landholders, many of whom were slave owners themselves, were not inclined to enlist a black man, and in so doing deprive the slave owner of his servant. As a sidenote to this, it might be noted that Thomas Jefferson, in the preliminary draft of the Declaration of Independence, had included a scathing comment on George III as continuing to promote the slave trade. According to Jefferson, in a letter years later, the passage had been

"truck out in complaiance to South Carolina and Georgia, who had never attempted to retrain the importation of laves, and who on the contrary till wihed to continue it."

![]() Another reason for the general reluctance toward enlisting blacks into the army, was the fact that many of the white settlers did not trust placing guns and other weapons in the hands of the blacks for fear of insurrection.

Another reason for the general reluctance toward enlisting blacks into the army, was the fact that many of the white settlers did not trust placing guns and other weapons in the hands of the blacks for fear of insurrection.

![]() A third reason weighing in against the enlistment of blacks in the army was voiced by General Philip Schuyler, who asked how the so-called Sons of Freedom could countenance being defended by men who were slaves.

A third reason weighing in against the enlistment of blacks in the army was voiced by General Philip Schuyler, who asked how the so-called Sons of Freedom could countenance being defended by men who were slaves.

![]() The majority of the opposition to enlisting blacks into the ranks of the Patriot armies came, quite understandably, from the southern colonies. None of the southern colonies, save Maryland and Virginia, permitted black men to be enlisted. In regard to the two exceptions, Maryland permitted slaves to be enlisted, but Virginia would allow only freemen to join her forces. The northern colonies, on the other hand, began quite early to actually enlist black men, whether slave or free. Massachusetts started enlisting blacks in 1777, Rhode Island began in 1778, and the rest of the northern colonies soon followed suit.

The majority of the opposition to enlisting blacks into the ranks of the Patriot armies came, quite understandably, from the southern colonies. None of the southern colonies, save Maryland and Virginia, permitted black men to be enlisted. In regard to the two exceptions, Maryland permitted slaves to be enlisted, but Virginia would allow only freemen to join her forces. The northern colonies, on the other hand, began quite early to actually enlist black men, whether slave or free. Massachusetts started enlisting blacks in 1777, Rhode Island began in 1778, and the rest of the northern colonies soon followed suit.

![]() The Continental Congress was not eager to enlist blacks; in fact, on 26 September, 1775 Edward Rutledge, a delegate from South Carolina, made a motion to have all the blacks discharged who were then currently in the ranks of the Continental Army. Rutledge was supported by most of the southern delegates, but the opposition to his proposal was strong and it was defeated.

The Continental Congress was not eager to enlist blacks; in fact, on 26 September, 1775 Edward Rutledge, a delegate from South Carolina, made a motion to have all the blacks discharged who were then currently in the ranks of the Continental Army. Rutledge was supported by most of the southern delegates, but the opposition to his proposal was strong and it was defeated.

![]() In regard to matters which concerned the army, the delegates to the Continental Congress placed much faith and trust in the opinion of General Washington and the armys other commanders. In the matter of enlisting blacks, the General and other officers were not inclined to approve the idea. The Continental Congress sent a letter dated 26 September, 1775 to General George Washington in which a number of subjects were questioned. Washington received the letter during his encampment at Cambridge. A meeting was held between Washington and his general officers on 08 October to discuss the various subjects, one of which regarded the enlistment of slaves or free blacks. The generals attending that meeting unanimously agreed that slaves should not be enlisted. They were not unanimous on the subject of enlisting free black men, but a majority voted against it.

In regard to matters which concerned the army, the delegates to the Continental Congress placed much faith and trust in the opinion of General Washington and the armys other commanders. In the matter of enlisting blacks, the General and other officers were not inclined to approve the idea. The Continental Congress sent a letter dated 26 September, 1775 to General George Washington in which a number of subjects were questioned. Washington received the letter during his encampment at Cambridge. A meeting was held between Washington and his general officers on 08 October to discuss the various subjects, one of which regarded the enlistment of slaves or free blacks. The generals attending that meeting unanimously agreed that slaves should not be enlisted. They were not unanimous on the subject of enlisting free black men, but a majority voted against it.

![]() Some historians have noted General Washingtons change in attitude toward the idea of black men serving in the army. In General Orders which he issued at Cambridge on 12 November, 1775, Washington stated:

Some historians have noted General Washingtons change in attitude toward the idea of black men serving in the army. In General Orders which he issued at Cambridge on 12 November, 1775, Washington stated:

"Neither Negroes, Boys unable to bare Arms, nor old men unfit to endure the datigues of the campaign, are to be inlited."

![]() In a letter dated 31 December, 1775 to the President of the Continental Congress, General Washington stated:

In a letter dated 31 December, 1775 to the President of the Continental Congress, General Washington stated:

"It has been repreented to me, that the free Negroes who have erved in this Army, are very much diatified at being dicarded. As it is to be apprehended that they may eek employ in the Miniterial Army, I have preumed to depart from the Reolution repecting them and have given licence for their being enlited, If this is diapproved by Congres I hall put a top to it."

![]() The Congress responded to Washington by passing a resolution during its session of 16 January, 1776, which simply stated:

The Congress responded to Washington by passing a resolution during its session of 16 January, 1776, which simply stated:

That the free negroes who have erved faithfully in the army at Cambridge, may be re-inlited therein, but no others.

![]() According to Mark M. Boatner, in his book, Encyclopedia Of The American Revolution, stated that "Washingtons army is said to have averaged about 50 Negroes per battalion..."

According to Mark M. Boatner, in his book, Encyclopedia Of The American Revolution, stated that "Washingtons army is said to have averaged about 50 Negroes per battalion..."

![]() There were 755 blacks in the Continental Army according to a return dated 24 August, 1778. Unfortunately, the British were beginning to show success in the South and it was feared that many of the black men there would be tempted to join their side. There were a number of instances in which that had already happened. One theory for the attraction the British army held for the blacks, especially the slaves, was that between the Americans and the British, the British were the lesser of two evils. If you were a slave and escaped, there was the very real possibility that if you were taken into the British army, you would never have to go back to your previous master. Joining the American army did not carry with it the same possibility.

There were 755 blacks in the Continental Army according to a return dated 24 August, 1778. Unfortunately, the British were beginning to show success in the South and it was feared that many of the black men there would be tempted to join their side. There were a number of instances in which that had already happened. One theory for the attraction the British army held for the blacks, especially the slaves, was that between the Americans and the British, the British were the lesser of two evils. If you were a slave and escaped, there was the very real possibility that if you were taken into the British army, you would never have to go back to your previous master. Joining the American army did not carry with it the same possibility.

![]() Perhaps the first instance of blacks serving in the British army was at the Battle of Great Bridge on 09 December, 1775. A force of Patriots under Colonel William Woodford successfully marched against Governor Dunmore, who had set up fortifications at the one end of the Great Bridge near Norfolk, Virginia. Dunmore held, in reserve, a unit composed of two hundred and thirty Ethiopians and Loyal Virginians.

Perhaps the first instance of blacks serving in the British army was at the Battle of Great Bridge on 09 December, 1775. A force of Patriots under Colonel William Woodford successfully marched against Governor Dunmore, who had set up fortifications at the one end of the Great Bridge near Norfolk, Virginia. Dunmore held, in reserve, a unit composed of two hundred and thirty Ethiopians and Loyal Virginians.

![]() In April of 1776, when British General Henry Clinton arrived at North Carolina, his army took in seventy-one runaway slaves. These black men were organized into a company called the Black Pioneers commanded by Lieutenant George Martin. The name came from the use of the word pioneer to refer to a non-soldier who assisted in the functioning of the army. The Black Pioneers accompanied Clinton when he headed northward to take command of New York City. Except for a period in which they were assigned to General Sir William Howes army when he occupied Philadelphia, the Black Pioneers remained under Clintons command and protection.

In April of 1776, when British General Henry Clinton arrived at North Carolina, his army took in seventy-one runaway slaves. These black men were organized into a company called the Black Pioneers commanded by Lieutenant George Martin. The name came from the use of the word pioneer to refer to a non-soldier who assisted in the functioning of the army. The Black Pioneers accompanied Clinton when he headed northward to take command of New York City. Except for a period in which they were assigned to General Sir William Howes army when he occupied Philadelphia, the Black Pioneers remained under Clintons command and protection.

![]() As was feared by many of the Americans, their black slaves were encouraged into running away by promises of freedom. Governor Dunmore issued A Proclamation on 14 November, 1775, in which freedom was promised to

As was feared by many of the Americans, their black slaves were encouraged into running away by promises of freedom. Governor Dunmore issued A Proclamation on 14 November, 1775, in which freedom was promised to

...all indentured Servants, Negroes or others (appertaining to Rebels)..that are able and willing to bear Arms, they joining His MAJESTYS Troops as oon as may be, for the more peedily reducing this Colony to a proper Sene of their Duty...

![]() Perhaps Dunmores Proclamation gave General Washington the motivation to reconsider his stance on the enlistment of black men into the Continental Army, and to write the letter to the Continental Congress on 31 December, 1775.

Perhaps Dunmores Proclamation gave General Washington the motivation to reconsider his stance on the enlistment of black men into the Continental Army, and to write the letter to the Continental Congress on 31 December, 1775.

![]() Clinton issued the Phillipsburgh Proclamation four years later, on 30 June, 1779, in which he granted sanctuary and freedom to any black slaves who ran away from their white masters and made it to the British lines.

Clinton issued the Phillipsburgh Proclamation four years later, on 30 June, 1779, in which he granted sanctuary and freedom to any black slaves who ran away from their white masters and made it to the British lines.

![]() According to the records of Commissioner John Cruden, nearly 5,000 ex-slaves were placed in the employ of the British army after the taking of Charleston, South Carolina in 1780.

According to the records of Commissioner John Cruden, nearly 5,000 ex-slaves were placed in the employ of the British army after the taking of Charleston, South Carolina in 1780.

![]() During the siege of Yorktown, it is believed that nearly 5,000 blacks left the region aboard British merchant ships bound for Jamaica.

During the siege of Yorktown, it is believed that nearly 5,000 blacks left the region aboard British merchant ships bound for Jamaica.

![]() When the British evacuated Savannah, Georgia in August, 1782, approximately 3,500 blacks were transported to first to Jamaica and then to St. Augustine in colonial East Florida.

When the British evacuated Savannah, Georgia in August, 1782, approximately 3,500 blacks were transported to first to Jamaica and then to St. Augustine in colonial East Florida.

![]() Charlestons evacuation resulted in 5,300 blacks being transported in December, 1782 to Jamaica and then to East Florida.

Charlestons evacuation resulted in 5,300 blacks being transported in December, 1782 to Jamaica and then to East Florida.

![]() When the war had formally ended with the Treaty of Paris signed, and the British were making preparations to evacuate New York City, the last city held by them, nearly 3,000 blacks, of which nearly 1,300 were men, waited to be transported along with the British from this country.

When the war had formally ended with the Treaty of Paris signed, and the British were making preparations to evacuate New York City, the last city held by them, nearly 3,000 blacks, of which nearly 1,300 were men, waited to be transported along with the British from this country.

![]() The foregoing figures from the various cities occupied by the British, reveal the effective-ness of Clintons offer of freedom. Some of the members of the Continental Congress foresaw such an exodus of blacks to the enemy, and urged their fellow members to enact legislation that would enable them to reverse that trend.

The foregoing figures from the various cities occupied by the British, reveal the effective-ness of Clintons offer of freedom. Some of the members of the Continental Congress foresaw such an exodus of blacks to the enemy, and urged their fellow members to enact legislation that would enable them to reverse that trend.

![]() During the 29 March, 1779 session of the Continental Congress, the report of the committee on the circumtances of the outhern tates, and the ways and means for their afety and defence was presented. In regard to the circumstances of South Carolina, it was stated:

During the 29 March, 1779 session of the Continental Congress, the report of the committee on the circumtances of the outhern tates, and the ways and means for their afety and defence was presented. In regard to the circumstances of South Carolina, it was stated:

That the State of South Carolina as repreented by the delegates of the aid State and by Mr. Huger, who has come hither at the requet of the governor of the aid State, on purpoe to explain the particular circumtances thereof, is unable to make any effectual efforts with militia, by reaon of the great proportion of citizens necesary to remain at home to prevent inurrections among the negroes, and to prevent the deertion of them to the enemy.

That the tate of the country and the great numbers of thoe people among them expoe the inhabitants to great danger from the endeavors of the enemy to excite them, either to revolt or to deert. That it is uggeted by the delegatea of the aid State, and by Mr. Huger, that a force might be raied in the aid State from among the negroes which would not only be formidable to the enemy from their numbers and the dicipline of which they would very readily admit, but would alo lesen the danger from revolts and deertions by detaching the mot vigorous and enterprizing from among the negroes... Whereupon,

Reolved, That it be recommended to the Governing Powers of the States of South Carolina and Georgia, to conider of the Necesity, and Utility of arming (if they hall with Congres think it expedient to take meaures for immediately} raiing a force of ----- able bodied Negroes, either for filling up the continental Battalions of thoe States, or for forming eparate Corps, to be command-ed by white Commisioned and NonCommi-sioned Officers, the commisioned officers to be appointed by the aid governing Powers repectively, or for both purpoes.

![]() A South Carolinian, John Laurens, was dispatched by the Congress to go to his home state to drum up support for the raising of three thousand black men. The South Carolina planters gave Laurens the cold shoulder.

A South Carolinian, John Laurens, was dispatched by the Congress to go to his home state to drum up support for the raising of three thousand black men. The South Carolina planters gave Laurens the cold shoulder.

![]() But what of the blacks, enlisted in the other states? The facts speak for themselves that black men contributed to the Patriot Cause as wholeheartedly as whites.

But what of the blacks, enlisted in the other states? The facts speak for themselves that black men contributed to the Patriot Cause as wholeheartedly as whites.

![]() On 19 April, 1775 the shot heard round the world was fired at Lexington, Massachusetts. The British moved on westward to the town of Concord, where they were engaged by rebel Patriots and repelled back to Boston. Following that encounter, a broadside was published. In that List of the Names of the Provincials who were Killed and Wounded in the late Engagement with His Majetys Troops at Concord, &c was the name of Prince Easterbrooks (A Negro Man). He was enlisted in Captain John Parkers Company, which was the first to engage the British at Lexington that morning. Peter Salem of Framingham, freed by his master so that he could serve with the local militia, was at Lexington on that day in April, 1775 also. It is believed that there were perhaps a dozen or more black men who stood with their white comrades on the battlefields of Lexington and Concord. The ones for whom we have names included not only the two listed above, but also: Isiah Bayoman of Stoneham, Pomp Blackman, Cato Bordman of Cambridge, Samuel Craft of Newton, Pompy of Braintree, Job Potama of Stoneham, Prince of Brookline, Cato Stedman of Cambridge, Cuff Whitemore of Arlington, and Cato Wood of Arlington.

On 19 April, 1775 the shot heard round the world was fired at Lexington, Massachusetts. The British moved on westward to the town of Concord, where they were engaged by rebel Patriots and repelled back to Boston. Following that encounter, a broadside was published. In that List of the Names of the Provincials who were Killed and Wounded in the late Engagement with His Majetys Troops at Concord, &c was the name of Prince Easterbrooks (A Negro Man). He was enlisted in Captain John Parkers Company, which was the first to engage the British at Lexington that morning. Peter Salem of Framingham, freed by his master so that he could serve with the local militia, was at Lexington on that day in April, 1775 also. It is believed that there were perhaps a dozen or more black men who stood with their white comrades on the battlefields of Lexington and Concord. The ones for whom we have names included not only the two listed above, but also: Isiah Bayoman of Stoneham, Pomp Blackman, Cato Bordman of Cambridge, Samuel Craft of Newton, Pompy of Braintree, Job Potama of Stoneham, Prince of Brookline, Cato Stedman of Cambridge, Cuff Whitemore of Arlington, and Cato Wood of Arlington.

![]() Two months after the engagement at Lexington and Concord, the British attacked the Patriot defences on Breeds and Bunker Hill. An episode that occurred during the battle was described by Dr. Jeremy Belknap in his diary:

Two months after the engagement at Lexington and Concord, the British attacked the Patriot defences on Breeds and Bunker Hill. An episode that occurred during the battle was described by Dr. Jeremy Belknap in his diary:

"A negro man belonging to Groton, took aim at Major Pitcairne as he was rallying the dipered Britih Troops, & hot him thro the head."

![]() That negro man belonging to Groton was noted by the contemporary historian, Samuel Swett as being Salem, a black soldier. The muster rolls taken at the time of the Battle of Bunker Hill contained notations beside fourteen mens names as either Negro or Mulatto.

That negro man belonging to Groton was noted by the contemporary historian, Samuel Swett as being Salem, a black soldier. The muster rolls taken at the time of the Battle of Bunker Hill contained notations beside fourteen mens names as either Negro or Mulatto.

![]() On the night of December 25/26 1776, General George Washington ferried his troops across the Delaware River to attack the Hessian soldiers in the town of Trenton, New Jersey. Along with the Patriots traveled at least one black man, Prince Whipple. He had been the slave of William Whipple, a delegate to the Second Continental Congress from New Hampshire, and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

On the night of December 25/26 1776, General George Washington ferried his troops across the Delaware River to attack the Hessian soldiers in the town of Trenton, New Jersey. Along with the Patriots traveled at least one black man, Prince Whipple. He had been the slave of William Whipple, a delegate to the Second Continental Congress from New Hampshire, and a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

![]() A black regiment raised in Rhode Island under the command of Colonel Christopher Greene displayed desperate valor in effectively repulsing three attacks by Hessians during the Battle of Rhode Island at Newport on 29 August, 1778. The regiments valor was described by a contemporary writer:

A black regiment raised in Rhode Island under the command of Colonel Christopher Greene displayed desperate valor in effectively repulsing three attacks by Hessians during the Battle of Rhode Island at Newport on 29 August, 1778. The regiments valor was described by a contemporary writer:

"There was a black regiment in the ame ituation. Yes, a regiment of negroes, fighting for our liberty and independence, - not a white man among them but the officers, - tationed in the ame dangerous and reponible poition. Had they been unfaithful, or given way before the enemy, all would have been lot. Three times in uccesion were they attacked, with mot deperate valor and fury, by well diciplined and veteran troops, and three times did they uccesfully repel the asault, and thus preerve our army from capture."

![]() Greenes regiment was the 1st Rhode Island Regiment. Rhode Island had led the way in creating segregated black regiments when, in January of 1778 it reassigned the 1st Rhode Island Regiment of the Continental Line to the 2nd Regiment, and then restablished the 1st Regiment entirely of blacks, albeit with white officers and non-commissioned officers. In order to fill the regiment, the state government purchased any and all slaves who wished to enlist from their owners.

Greenes regiment was the 1st Rhode Island Regiment. Rhode Island had led the way in creating segregated black regiments when, in January of 1778 it reassigned the 1st Rhode Island Regiment of the Continental Line to the 2nd Regiment, and then restablished the 1st Regiment entirely of blacks, albeit with white officers and non-commissioned officers. In order to fill the regiment, the state government purchased any and all slaves who wished to enlist from their owners.

![]() The promise of emancipation following the war was a great incentive to the slaves. During the course of the war between two hundred and twenty five and two hundred and fifty black men joined the 1st Rhode Island Regiment. This black regiment would not only distinguish itself in the Battle of Rhode Island but also at Red Point, at New York City in 1781, at Oswego and at Yorktown.

The promise of emancipation following the war was a great incentive to the slaves. During the course of the war between two hundred and twenty five and two hundred and fifty black men joined the 1st Rhode Island Regiment. This black regiment would not only distinguish itself in the Battle of Rhode Island but also at Red Point, at New York City in 1781, at Oswego and at Yorktown.

![]() Rhode Island was not the only New England state to see the value in allowing its black residents to serve in the army. Connecticut, believed to have had the largest population of blacks north of the Mason-Dixon line, passed two pieces of legislation in 1777 to allow blacks to enter the army. The first stated that any two men who procured a substitute would be exempted from the draft. The second stated that masters who freed their slaves in order that they might serve in the army would be relieved of all future obligation to support those slaves. The legislation was welcomed by whites and blacks alike. A master and his son were guaranteed exemption, by providing a slave as a substitute in their place. The slave often regarded the deal as fair because it meant he would gain his freedom upon the conclusion of the war. The Second Company of the Fourth Regiment of the Connecticut Continental Line was composed entirely of black men.

Rhode Island was not the only New England state to see the value in allowing its black residents to serve in the army. Connecticut, believed to have had the largest population of blacks north of the Mason-Dixon line, passed two pieces of legislation in 1777 to allow blacks to enter the army. The first stated that any two men who procured a substitute would be exempted from the draft. The second stated that masters who freed their slaves in order that they might serve in the army would be relieved of all future obligation to support those slaves. The legislation was welcomed by whites and blacks alike. A master and his son were guaranteed exemption, by providing a slave as a substitute in their place. The slave often regarded the deal as fair because it meant he would gain his freedom upon the conclusion of the war. The Second Company of the Fourth Regiment of the Connecticut Continental Line was composed entirely of black men.

![]() Despite the need for more troops, and the apparent value they had brought to the Continental Army after some four or five years of service, there were still individuals in power, including General Washington, who were against allowing the blacks too much recognition. As noted previously, his attitude had changed, but even though Washington was not completely against blacks serving in the Continental Army, he just wanted to ensure that they did not gain too much freedom.

Despite the need for more troops, and the apparent value they had brought to the Continental Army after some four or five years of service, there were still individuals in power, including General Washington, who were against allowing the blacks too much recognition. As noted previously, his attitude had changed, but even though Washington was not completely against blacks serving in the Continental Army, he just wanted to ensure that they did not gain too much freedom.

![]() General Washington, sent a letter to Major General William Heath, dated 29 June, 1780, in which he was discussed the regiments of the Continental Line from the province of Rhode Island. In that letter he noted:

General Washington, sent a letter to Major General William Heath, dated 29 June, 1780, in which he was discussed the regiments of the Continental Line from the province of Rhode Island. In that letter he noted:

"The objection to joining Greenes Regiment may be removed by dividing the Blacks in uch a manner between the two, as to abolih the name and appearance of a Black Corps."

![]() General Washington did not provide an explanation of his desire to abolish the name and appearance of a Black Corps in the letter to General Heath. Washington would, six years later advocate abolition of slavery in another letter. On 09 September, 1786 he wrote a letter to John Mercer in which he stated, in reply to a previous question from Mercer:

General Washington did not provide an explanation of his desire to abolish the name and appearance of a Black Corps in the letter to General Heath. Washington would, six years later advocate abolition of slavery in another letter. On 09 September, 1786 he wrote a letter to John Mercer in which he stated, in reply to a previous question from Mercer:

"I never mean (unles ome particular circumtance hould compel me to it) to poses another lave by purchae; it being among my firt wihes to ee ome plan adopted, by which lavery in this country may be abolihed by low, ure, and imperceptible degrees."

![]() The Southern aristocrats / planters objections to emancipating their slaves were not shared by their northern sister states. The first step was taken by the predominantly Quaker legislature of Pennsylvania when it enacted a law granting the gradual abolition of slavery within the states bounds on 01 March, 1780. Although not abolishing slavery entirely and all at once, the law gave freedom to the children of then existing slaves when they would reach the age of twenty-eight, and no children born to slaves after that date would be considered slaves themselves. The state of Massachusetts followed Pennsylvanias lead by enacting a similar, but more far-reaching law when she abolished slavery altogether, later that same year. The other northern states in turn followed Pennsylvania and Massachusetts lead with Vermont and New Hampshire passing legislation to abolish slavery completely, and Connecticut and Rhode Island calling for gradual abolition, all in 1784. New York would pass similar legislation in 1799.

The Southern aristocrats / planters objections to emancipating their slaves were not shared by their northern sister states. The first step was taken by the predominantly Quaker legislature of Pennsylvania when it enacted a law granting the gradual abolition of slavery within the states bounds on 01 March, 1780. Although not abolishing slavery entirely and all at once, the law gave freedom to the children of then existing slaves when they would reach the age of twenty-eight, and no children born to slaves after that date would be considered slaves themselves. The state of Massachusetts followed Pennsylvanias lead by enacting a similar, but more far-reaching law when she abolished slavery altogether, later that same year. The other northern states in turn followed Pennsylvania and Massachusetts lead with Vermont and New Hampshire passing legislation to abolish slavery completely, and Connecticut and Rhode Island calling for gradual abolition, all in 1784. New York would pass similar legislation in 1799.

![]() It should lastly be noted that the black Patriots seldom received the compensation they were deserving of, other than the release of servitude to their previous masters. When, on 13 June, 1783 the 1st Rhode Island Regiment of the Continental Line was discharged, the men were simply told to go home. They would get no pay.

It should lastly be noted that the black Patriots seldom received the compensation they were deserving of, other than the release of servitude to their previous masters. When, on 13 June, 1783 the 1st Rhode Island Regiment of the Continental Line was discharged, the men were simply told to go home. They would get no pay.